Living Epistles Read and Known if All Men

Ruins of forecourt of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, where "know thyself" was one time said to exist inscribed

Allegorical painting from the 17th century with text Nosce te ipsum

The Ancient Greek aphorism "know thyself" (Greek: γνῶθι σεαυτόν , transliterated: gnōthi seauton ; likewise ... σαυτόν … sauton with the ε contracted) is one of the Delphic maxims and was the first of three maxims inscribed in the pronaos (forecourt) of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi according to the Greek writer Pausanias (x.24.1).[1] The two maxims that followed "know thyself" were "nothing to excess" and "certainty brings insanity".[ii] In Latin the phrase, "know thyself", is given every bit nosce te ipsum [3] or temet nosce .[4]

The maxim, or aphorism, "know thyself" has had a diverseness of meanings attributed to it in literature, and over fourth dimension, as in early ancient Greek the phrase meant "know thy measure".[5]

Attribution [edit]

The Greek aphorism has been attributed to at to the lowest degree the following ancient Greek sages:

- Bias of Priene[6]

- Chilon of Sparta[7]

- Cleobulus of Lindus[6]

- Heraclitus[viii]

- Myson of Chenae[6]

- Periander[9]

- Pittacus of Mytilene[6]

- Pythagoras[10]

- Plato[11]

- Solon of Athens[half-dozen]

- Thales of Miletus[12]

Diogenes Laërtius attributes it to Thales (Lives I.40), simply too notes that Antisthenes in his Successions of Philosophers attributes it to Phemonoe, a mythical Greek poet, though admitting that it was appropriated by Chilon. In a discussion of moderation and self-awareness, the Roman poet Juvenal quotes the phrase in Greek and states that the precept descended e caelo (from heaven) (Satires xi.27). The 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia the Suda recognized Chilon[7] and Thales[12] as the sources of the maxim "Know Thyself".

The authenticity of all such attributions is hundred-to-one; according to Parke and Wormell (1956), "The actual authorship of the three maxims ready on the Delphian temple may be left uncertain. About likely they were popular proverbs, which tended subsequently to be attributed to particular sages."[xiii] [14]

Usage [edit]

Listed chronologically:

Past Aeschylus [edit]

The ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus uses the maxim "know thyself" in his play Prometheus Bound. The play, near a mythological sequence, thereby places the maxim within the context of Greek mythology. In this play, the demi-god Prometheus first runway at the Olympian gods, and confronting what he believes to exist the injustice of his having been jump to a cliffside by Zeus, king of the Olympian gods. The demi-god Oceanus comes to Prometheus to reason with him, and cautions him that he should "know thyself".[15] In this context, Oceanus is telling Prometheus that he should know better than to speak ill of the one who decides his fate and appropriately, perhaps he should meliorate know his identify in the "groovy order of things".

By Socrates [edit]

One of Socrates'south students, the historian Xenophon, described some of the instances of Socrates's apply of the Delphic maxim "Know Thyself" in his history titled: Memorabilia. In this writing, Xenophon portrayed his instructor's utilize of the maxim equally an organizing theme for Socrates's lengthy dialogue with Euthydemus.[xvi]

By Plato [edit]

Plato, another student of Socrates, employs the maxim "Know Thyself" extensively past having the graphic symbol of Socrates utilize it to motivate his dialogues. Benjamin Jowett'south index to his translation of the Dialogues of Plato lists six dialogues which discuss or explore the Delphic maxim: "know thyself". These dialogues (and the Stephanus numbers indexing the pages where these discussions begin) are Charmides (164D), Protagoras (343B), Phaedrus (229E), Philebus (48C), Laws (II.923A), Alcibiades I (124A, 129A, 132C).[17]

In Plato's Charmides, Critias argues that "succeeding sages who added 'never likewise much', or, 'give a pledge, and evil is nigh at hand', would appear to have so misunderstood them; for they imagined that 'know thyself!' was a piece of advice which the god gave, and not his salutation of the worshippers at their first coming in; and they dedicated their own inscription under the idea that they too would give equally useful pieces of advice."[18] In Critias' stance "know thyself!" was an admonition to those entering the sacred temple to remember or know their place and that "know thyself!" and "be temperate!" are the same.[19] In the residual of the Charmides, Plato has Socrates lead a longer inquiry equally to how we may gain cognition of ourselves.

In Plato'south Phaedrus, Socrates uses the maxim "know thyself" every bit his caption to Phaedrus to explain why he has no time for the attempts to rationally explicate mythology or other far flung topics. Socrates says, "But I have no leisure for them at all; and the reason, my friend, is this: I am non notwithstanding able, as the Delphic inscription has it, to know myself; so it seems to me ridiculous, when I do non yet know that, to investigate irrelevant things."[20]

In Plato's Protagoras, Socrates lauds the authors of pithy and curtailed sayings delivered precisely at the right moment and says that Lacedaemon, or Sparta, educates its people to that end. Socrates lists the Seven Sages as Thales, Pittacus, Bias, Solon, Cleobulus, Myson, and Chilon, who he says are gifted in that Lacedaemonian fine art of concise words "twisted together, like a bowstring, where a slight try gives great force".[21] Socrates says examples of them are, "the far-famed inscriptions, which are in all men's mouths—'Know thyself', and 'Nothing too much'".[22] Having lauded the maxims, Socrates then spends a great deal of time getting to the bottom of what one of them means, the saying of Pittacus, "Difficult is it to be practiced." The irony here is that although the sayings of Delphi behave "nifty force", information technology is not articulate how to live life in accord with their meanings. Although, the curtailed and broad nature of the sayings suggests the active partaking in the usage and personal discovery of each maxim; as if the intended nature of the saying lay not in the words just the self-reflection and self-referencing of the person thereof.

In Plato's Philebus dialogue, Socrates refers back to the same usage of "know thyself" from Phaedrus to build an instance of the ridiculous for Protarchus. Socrates says, equally he did in Phaedrus, that people make themselves appear ridiculous when they are trying to know obscure things before they know themselves.[23] Plato as well alluded to the fact that understanding "thyself" would have a greater yielded factor of agreement the nature of a human. Syllogistically, understanding oneself would enable thyself to take an understanding of others as a result.

Later usage [edit]

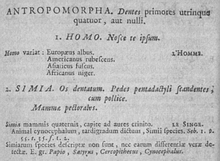

Detail from the 6th edition of Linnaeus' Systema Naturae (1748). "HOMO. Nosce te ipsum."

The Suda, a 10th-century encyclopedia of Greek knowledge, states: "the proverb is applied to those whose boasts exceed what they are",[7] and that "know thyself" is a warning to pay no attention to the opinion of the multitude.[24]

Self-cognition was an important concept in the writings of the 12-13th century Castilian Sufi Ibn Arabi. He distinguished between various philosophical and mystical meanings of "Know Thyself" and the hadith "Who knows himself, knows his Lord."[25]

Ane piece of work by the Medieval philosopher Peter Abelard is titled Scito te ipsum ("know yourself") or Ethica.

From 1539 onward, the phrase nosce te ipsum and its Latin variants were used in the anonymous texts written for anatomical avoiding sheets printed in Venice too as for afterward anatomical atlases printed throughout Europe. The 1530s fugitive sheets are the first instances in which the phrase was applied to knowledge of the human being body attained through dissection.[26]

In 1600, in his play Hamlet, Shakespeare writes, "To thine ain self be true."

In 1651, Thomas Hobbes used the term nosce teipsum which he translated every bit "read thyself" in his piece of work The Leviathan. He was responding to a pop philosophy at the time that you can acquire more by studying others than y'all tin can from reading books. He asserts that i learns more by studying oneself: particularly the feelings that influence our thoughts and motivate our actions. As Hobbes states, "but to teach u.s.a. that for the similitude of the thoughts and passions of 1 man, to the thoughts and passions of another, whosoever looketh into himself and considereth what he doth when he does call back, opine, reason, hope, fear, etc., and upon what grounds; he shall thereby read and know what are the thoughts and passions of all other men upon the similar occasions."[27]

In 1734, Alexander Pope wrote a poem entitled "An Essay on Man, Epistle 2", which begins "Know then thyself, assume not God to scan, The proper study of mankind is Man."[28]

In 1735, Carl Linnaeus published the first edition of Systema Naturae in which he described humans (Homo) with the uncomplicated phrase "Nosce te ipsum".[29]

In 1750, Benjamin Franklin, in his Poor Richard'south Almanack, observed the great difficulty of knowing ane'due south self, with: "There are three Things extremely hard, Steel, a Diamond, and to know i's self."[30]

In 1754, Jean-Jacques Rousseau lauded the "inscription of the Temple at Delphi" in his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality.

In 1831, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a poem titled "Γνώθι Σεαυτόν", or Gnothi Seauton ('Know Thyself'), on the theme of "God in thee". The poem was an anthem to Emerson's belief that to "know thyself" meant knowing the God that Emerson felt existed within each person.[31]

In 1832, Samuel T. Coleridge wrote a poem titled "Self Cognition" in which the text centers on the Delphic maxim "Know Thyself" get-go "Gnôthi seauton!—and is this the prime number And heaven-sprung adage of the olden fourth dimension!—" and ending with "Ignore thyself, and strive to know thy God!" Coleridge'south text references JUVENAL, xi. 27.[32]

In 1857, Allan Kardec asks in The Spirits Book (question 919): "What is the most effective method for guaranteeing cocky-comeback and resisting the allure of wrongdoing?" and obtains the respond from the Spirits "A philosopher of antiquity once said, 'Know thyself'".[33] Acknowledging the wisdom of the maxim, he then asks almost the means of acquiring self-noesis, obtaining a detailed reply with practical instructions and philosophical-moral considerations.

In 1902, Hugo von Hofmannsthal had his 16th-century alter ego in his alphabetic character to Francis Bacon mention a volume he intended to call Nosce te ipsum.

In 1978 Idries Shah wrote in Learning How to Learn, p. 38, "People have to know more than about themselves earlier they take on what are so often misconceived projects." In 1997 he explained "Know Thyself" thus in The Commanding Self, p. 15, "'He who knows himself, knows his Lord' ways, amongst other things, that self-deception prevents cognition... The first cocky about which to obtain noesis is the secondary, faux self which stands in the way..." The theme of knowing oneself and knowing God is besides featured in the above citations from Ibn Arabi, Pope, Coleridge and Emerson, in different means.

The Wachowskis used one of the Latin versions (temet nosce) of this aphorism as inscription over the Oracle's kitchen doorway in their movies The Matrix (1999)[34] and The Matrix Revolutions (2003).[35] The transgender character Nomi in the Netflix show Sense8, over again directed by The Wachowskis, has a tattoo on her arm with the Greek version of this phrase.

"Know Thyself" is the motto of Hamilton College of Lyceum International School (Nugegoda, Sri Lanka) and of İpek University (Ankara, Turkey).[36] The Latin phrase "Nosce te ipsum" is the motto of Landmark College.

Nosce te ipsum is too the motto for the Scottish clan Thompson. Information technology is featured on the family crest or coat of artillery.[37]

In other cultures [edit]

Knowing the Cocky is a core principle towards spiritual liberation or Moksha in Indian philosophical traditions, including Advaita Vedanta. In the Upanishads, it appears every bit "Atmanam Viddhi", that literally translates to "know thyself". The idea is reflected through the four key statements known as Mahavakya, found in the four Vedas, which form the foundations of Vedanta philosophy.

In The Fine art of State of war, the maxim 知彼知己,百战不殆 means "know others and know thyself, and you lot volition not exist endangered by innumerable battles". In this maxim by Sun Zi (孙子, Sun Tze), the idea of knowing oneself is paramount.

See also [edit]

- Delphic maxims

- I know that I know aught

- Introspection

- Jnana

- Philosophy of self

- Cocky-knowledge (psychology)

- The Art of State of war

- Mahāvākyas

References [edit]

- ^ "Pausanias, Clarification of Greece, Phocis and Ozolian Locri, chapter 24". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Plato Charmides 165

- ^ "Nosce te ipsum - Definition and More than from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 2010-08-13. Retrieved xvi March 2011.

- ^ "AllExperts.com: temet nosce". allexperts.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 17 Feb 2013.

- ^ Wilkins, Eliza G. (April 1927). "ΕΓΓΥΑ, ΠΑΡΑ ΔΑΤΗ in Literature" (PDF). Classical Philology. Academy of Chicago Press. 22 (2): 121–135. doi:x.1086/360881. JSTOR 263511. S2CID 162666822.

- ^ a b c d eastward "Plato, Protagoras, department 343a". world wide web.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ a b c "SOL Search". www.cs.uky.edu.

- ^ Doctoral thesis, "Know Thyself in Greek and Latin Literature," Eliza G. Wilkens, U. Chi, 1917, p. 12 (online).

- ^ Pausanias 10.24.1 mentions a controversy over whether Periander should be listed as the seventh sage instead of Myson. Only Socrates who is cited by Pausanias as his source supports Myson. Paus. 10.24

- ^ Vico, Giambattista; Visconti, Gian Galeazzo (1993). On humanistic pedagogy: (six inaugural orations, 1699-1707) . Half dozen Countdown Orations, 1699-1707 From the Definitive Latin Text, Introduction, and Notes of Gian Galeazzo Visconti. Cornell Academy Press. p. iv. ISBN0801480876.

- ^ "Plato, Philebus, department 48c". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ a b "SOL Search". www.cs.uky.edu.

- ^ H. Parke and D. Wormell, The Delphic Oracle, (Basil Blackwell, 1956), vol. 1, p. 389.

- ^ Dempsey, T., Delphic Oracle: Its Early History, Influence & Fall, Oxford: B.H. Blackwell, 1918. With a prefatory notation by R. S. Conway. Cf. pp.141-142 (Alternative source for book at Internet Annal in diverse formats)

- ^ Aeschylus, Prometheys Bound, v. 309: γίγνωσκε σαυτὸν.

- ^ "Xenophon, Memorabilia, Book 4, chapter two, section 24". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Plato, The Dialogues of Plato translated into English with Analyses and Introductions by Benjamin Jowett, M.A. in Five Volumes. 3rd edition revised and corrected (Oxford University Printing, 1892), (See Index: Knowledge; 'know thyself' at Delphi).

- ^ "Plato, Charmides, section 165a". world wide web.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "Plato, Charmides, section 164e". world wide web.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "Plato, Phaedrus, department 229e". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "Plato, Protagoras, section 343a". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "Plato, Protagoras, section 343b". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "Plato, Philebus, section 48c". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "SOL Search". www.cs.uky.edu.

- ^ Know Yourself, According To Qur'an And Sunnah: Ibn Arabi's View, Journal of Philosophical Theological Research Autumn 2007, Volume 9, Number 1 (33); Page(s) 6 to 22, https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?FID=105220073301

- ^ William Schupbach, The Paradox of Rembrandt's "Anatomy of Dr. Tulp" (Wellcome Found for the History of Medicine: London, 1982), pp. 67–68

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas. "The Leviathan". Civil peace and social unity through perfect government. Oregon Country University: Phl 302, Neat Voyages: the History of Western Philosophy from 1492–1776, Wintertime 1997. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved vi January 2011.

- ^ "Alexander Pope begins his Essay on Man Epistle 2 'Know and so thyself'".

- ^ Maxwell, Mary (January 1984). Human being Evolution: A Philosophical Anthropology. ISBN9780709917922.

- ^ Franklin, Benjamin (January 31, 1904). "Autobiography: Poor Richard. Letters". D. Appleton – via Google Books.

- ^ "Emerson -Poesy- Gnothi Seauton". archive.vcu.edu.

- ^ Samuel T. Coleridge wrote the poem "Self Knowledge" discussing Gnôthi seauton or know thyself.

- ^ "O Livro dos Espíritos > Parte terceira — Das leis morais > Capítulo XII — Da perfeição moral > Conhecimento de si mesmo". kardecpedia.com.

- ^ See occurrences on Google Books.

- ^ McGrath, Patrick (10 January 2011). "'Know Thyself'. The nearly important fine art lesson of all". patrickmcgrath . Retrieved three Oct 2013.

- ^ ipek.edu.tr.

- ^ "Thompson Surname, Family Crest & Coats of Artillery". Firm of Names . Retrieved xix April 2017.

External links [edit]

- Gnothi sauton at Binghamton Academy

- "The Examined Life", BBC Radio iv discussion with A.C. Grayling, Janet Radcliffe & Julian Baggini (In Our Time, May nine, 2002)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Know_thyself

0 Response to "Living Epistles Read and Known if All Men"

Post a Comment