Why Doesnt My Back to Eden Garden Grow

Biblical garden of God

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (Hebrew: גַּן־עֵדֶן – gan-ʿĒḏen) or Garden of God (גַּן־יְהֹוָה – gan-YHWH), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2-3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31.[1] [2]

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Genesis as the source of four tributaries. Among scholars who consider it to have been real, there have been various suggestions for its location:[3] at the head of the Persian Gulf, in southern Mesopotamia (now Iraq) where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers run into the sea;[4] and in Armenia.[5] [6] [7]

Like the Genesis flood narrative, the Genesis creation narrative and the account of the Tower of Babel, the story of Eden echoes the Mesopotamian myth of a king, as a primordial man, who is placed in a divine garden to guard the tree of life.[8] The Hebrew Bible depicts Adam and Eve as walking around the Garden of Eden naked due to their sinlessness.[9]

Mentions of Eden are also made in the Bible elsewhere in Genesis,[10] in Isaiah 51:3,[11] Ezekiel 36:35,[12] and Joel 2:3;[13] Zechariah 14 and Ezekiel 47 use paradisical imagery without naming Eden.[14]

The name derives from the Akkadian edinnu, from a Sumerian word edin meaning "plain" or "steppe", closely related to an Aramaic root word meaning "fruitful, well-watered".[2] Another interpretation associates the name with a Hebrew word for "pleasure"; thus the Vulgate reads "paradisum voluptatis" in Genesis 2:8 and Douay–Rheims, following, has the wording "And the Lord God had planted a paradise of pleasure".[15]

Biblical narratives [edit]

Genesis [edit]

Expulsion from Paradise, painting by James Tissot (c. 1896–1902)

The second part of the Genesis creation narrative, Genesis 2:4–3:24, opens with YHWH-Elohim (translated here "the LORD God", see Names of God in Judaism) creating the first man (Adam), whom he placed in a garden that he planted "eastward in Eden".[16] "And out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil."[17]

The man was free to eat from any tree in the garden except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Last of all, God made a woman (Eve) from a rib of the man to be a companion for the man. In chapter three, the man and the woman were seduced by the serpent into eating the forbidden fruit, and they were expelled from the garden to prevent them from eating of the tree of life, and thus living forever. Cherubim were placed east of the garden, "and a flaming sword which turned every way, to guard the way of the tree of life".[18]

Genesis 2:10-14[19] lists four rivers in association with the garden of Eden: Pishon, Gihon, Hiddekel (the Tigris), and Phirat (the Euphrates). It also refers to the land of Cush—translated/interpreted as Ethiopia, but thought by some to equate to Cossaea, a Greek name for the land of the Kassites.[20] These lands lie north of Elam, immediately to the east of ancient Babylon, which, unlike Ethiopia, does lie within the region being described.[21] In Antiquities of the Jews, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus identifies the Pishon as what "the Greeks called Ganges" and the Geon (Gehon) as the Nile.[22]

According to Lars-Ivar Ringbom the paradisus terrestris is located in Takab in northwestern Iran.[23]

Ezekiel [edit]

In Ezekiel 28:12-19[24] the prophet Ezekiel the "son of man" sets down God's word against the king of Tyre: the king was the "seal of perfection", adorned with precious stones from the day of his creation, placed by God in the garden of Eden on the holy mountain as a guardian cherub. But the king sinned through wickedness and violence, and so he was driven out of the garden and thrown to the earth, where now he is consumed by God's fire: "All those who knew you in the nations are appalled at you, you have come to a horrible end and will be no more." (v.19).

According to Terje Stordalen, the Eden in Ezekiel appears to be located in Lebanon.[25] "[I]t appears that the Lebanon is an alternative placement in Phoenician myth (as in Ez 28,13, III.48) of the Garden of Eden",[26] and there are connections between paradise, the Garden of Eden and the forests of Lebanon (possibly used symbolically) within prophetic writings.[27] Edward Lipinski and Peter Kyle McCarter have suggested that the garden of the gods, the oldest Sumerian analog of the Garden of Eden, relates to a mountain sanctuary in the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges.[28]

Proposed locations [edit]

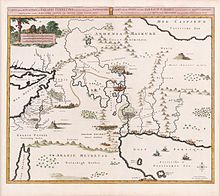

Map showing the rivers in the Middle East known in English as the Tigris and Euphrates

The location of Eden is described in Genesis 2:10–14:[29]

And a river went out of Eden to water the garden; and from thence it was parted, and became four heads. The name of the first is Pishon; that is it which compasseth the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold; and the gold of that land is good; there is bdellium and the onyx stone. And the name of the second river is Gihon; the same is it that compasseth the whole land of Cush. And the name of the third river is Tigris; that is it which goeth toward the east of Asshur. And the fourth river is the Euphrates.

Suggestions for the location of the Garden of Eden include[3] the head of the Persian Gulf, as argued by Juris Zarins, in southern Mesopotamia (now Iraq and Kuwait) where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers run into the sea;[4] and in the Armenian Highlands or Armenian Plateau.[5] [30] [6] [7] British archaeologist David Rohl locates it in Iran, and in the vicinity of Tabriz, but this suggestion has not caught on with scholarly sources.[31]

On his third voyage to the Americas, in 1498, Christopher Columbus thought he may have reached the Earthly Paradise upon first seeing the South American mainland.[32]

Some religious groups have believed the location of the garden to be local to them, outside of the Middle East. Some early leaders of Mormonism held that it was located in Jackson County, Missouri.[33] The 20th-century Panacea Society believed it was located at the site of their home town of Bedford, England,[34] while preacher Elvy E. Callaway believed it was on the Apalachicola River in Florida, near the town of Bristol.[35] Some suggested that the location is in Jerusalem.[36]

Parallel concepts [edit]

Map by Pierre Mortier, 1700, based on theories of Pierre Daniel Huet, Bishop of Avranches. A caption in French and Dutch reads: Map of the location of the terrestrial paradise, and of the country inhabited by the patriarchs, laid out for the good understanding of sacred history, by M. Pierre Daniel Huet

- Dilmun in the Sumerian story of Enki and Ninhursag is a paradisaical abode[37] of the immortals, where sickness and death were unknown.[38]

- The garden of the Hesperides in Greek mythology was somewhat similar to the Jewish concept of the Garden of Eden, and by the 16th century a larger intellectual association was made in the Cranach painting. In this painting, only the action that takes place there identifies the setting as distinct from the Garden of the Hesperides, with its golden fruit.

- The word "paradise" entered English from the French paradis, inherited from the Latin paradisus, from Greek parádeisos (παράδεισος), from an Old Iranian form, from Proto-Iranian*parādaiĵah- "walled enclosure", whence Old Persian 𐎱𐎼𐎭𐎹𐎭𐎠𐎶 p-r-d-y-d-a-m /paridaidam/, Avestan 𐬞𐬀𐬌𐬭𐬌⸱𐬛𐬀𐬉𐬰𐬀 pairi-daêza-. The literal meaning of this Eastern Old Iranian language word is "walled (enclosure)", from pairi- 'around' (cognate with Greek περί, English peri- of identical meaning) and -diz "to make, form (a wall), build" (cognate with Greek τεῖχος 'wall'). The word's etymology is ultimately derived from a PIE root*dheigʷ "to stick and set up (a wall)", and *per"around". By the 6th/5th century BCE, the Old Iranian word had been borrowed into Assyrian pardesu"domain". It subsequently came to indicate the expansive walled gardens of the First Persian Empire, and was subsequently borrowed into Greek as παράδεισος parádeisos "park for animals" in the Anabasis of the early 4th century BCE Athenian Xenophon, Aramaic as pardaysa "royal park", and Hebrew as פַּרְדֵּס pardes, "orchard" (appearing thrice in the Tanakh; in the Song of Solomon (Song of Songs 4:13), Ecclesiastes (Ecclesiastes 2:5) and Nehemiah(Nehemiah 2:8)). In the Septuagint (3rd–1st centuries BCE), Greek παράδεισος parádeisoswas used to translate both Hebrew פרדס pardesand Hebrew גן gan, "garden" (e.g. (Genesis 2:8, Ezekiel 28:13): it is from this usage that the use of "paradise" to refer to the Garden of Eden derives. The same usage also appears in Arabic and in the Quran as firdaws فردوس. The idea of a walled enclosure was not preserved in most Iranian usage, and generally came to refer to a plantation or other cultivated area, not necessarily walled. For example, the Old Iranian word survives as Pardis in New Persian as well as its derivative pālīz (or "jālīz"), which denotes a vegetable patch. The word "pardes" occurs three times in the Hebrew Bible, but always in contexts other than a connection with Eden: in the Song of Solomon iv. 13: "Thy plants are an orchard (pardes) of pomegranates, with pleasant fruits; camphire, with spikenard"; Ecclesiastes 2. 5: "I made me gardens and orchards (pardes), and I planted trees in them of all kind of fruits"; and in Nehemiah ii. 8: "And a letter unto Asaph the keeper of the king's orchard (pardes), that he may give me timber to make beams for the gates of the palace which appertained to the house, and for the wall of the city." In these examples pardes clearly means "orchard" or "park", but in the apocalyptic literature and in the Talmud "paradise" gains its associations with the Garden of Eden and its heavenly prototype, and in the New Testament "paradise" becomes the realm of the blessed (as opposed to the realm of the cursed) among those who have already died, with literary Hellenistic influences.

Other views [edit]

Jewish eschatology [edit]

In the Talmud and the Jewish Kabbalah,[39] the scholars agree that there are two types of spiritual places called "Garden in Eden". The first is rather terrestrial, of abundant fertility and luxuriant vegetation, known as the "lower Gan Eden" (gan = garden). The second is envisioned as being celestial, the habitation of righteous, Jewish and non-Jewish, immortal souls, known as the "higher Gan Eden". The rabbis differentiate between Gan and Eden. Adam is said to have dwelt only in the Gan, whereas Eden is said never to be witnessed by any mortal eye.[39]

According to Jewish eschatology,[40] [41] the higher Gan Eden is called the "Garden of Righteousness". It has been created since the beginning of the world, and will appear gloriously at the end of time. The righteous dwelling there will enjoy the sight of the heavenly chayot carrying the throne of God. Each of the righteous will walk with God, who will lead them in a dance. Its Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants are "clothed with garments of light and eternal life, and eat of the tree of life" (Enoch 58,3) near to God and His anointed ones.[41] This Jewish rabbinical concept of a higher Gan Eden is opposed by the Hebrew terms gehinnom [42] and sheol, figurative names for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism, a place envisioned as being at the greatest possible distance from heaven.[43]

In modern Jewish eschatology it is believed that history will complete itself and the ultimate destination will be when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.[44]

[edit]

In the 1909 book Legends of the Jews, Louis Ginzberg compiled Jewish legends found in rabbinic literature. Among the legends are ones about the two Gardens of Eden. Beyond Paradise is the higher Gan Eden, where God is enthroned and explains the Torah to its inhabitants. The higher Gan Eden contains three hundred and ten worlds and is divided into seven compartments. The compartments are not described, though it is implied that each compartment is greater than the previous one and is joined based on one's merit. The first compartment is for Jewish martyrs, the second for those who drowned, the third for "Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai and his disciples," the fourth for those whom the cloud of glory carried off, the fifth for penitents, the sixth for youths who have never sinned; and the seventh for the poor who lived decently and studied the Torah.

In chapter two, Legends of the Jews gives a brief description of the lower Gan Eden. The tree of knowledge is a hedge around the tree of life, which is so vast that "it would take a man five hundred years to traverse a distance equal to the diameter of the trunk". From beneath the trees flow all the world's waters in the form of four rivers: Tigris, Nile, Euphrates, and Ganges. After the fall of man, the world was no longer irrigated by this water. While in the garden, though, Adam and Eve were served meat dishes by angels and the animals of the world understood human language, respected mankind as God's image, and feared Adam and Eve. When one dies, one's soul must pass through the lower Gan Eden in order to reach the higher Gan Eden. The way to the garden is the Cave of Machpelah that Adam guards. The cave leads to the gate of the garden, guarded by a cherub with a flaming sword. If a soul is unworthy of entering, the sword annihilates it. Within the garden is a pillar of fire and smoke that extends to the higher Gan Eden, which the soul must climb in order to reach the higher Gan Eden.

Islamic view [edit]

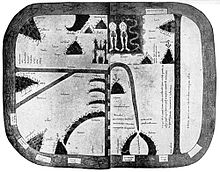

Mozarabic world map from 1109 with Eden in the East (at top)

The term jannāt ʿadni ("Gardens of Eden" or "Gardens of Perpetual Residence") is used in the Qur'an for the destination of the righteous. There are several mentions of "the Garden" in the Qur'an,[46] while the Garden of Eden, without the word ʿadn,[47] is commonly the fourth layer of the Islamic heaven and not necessarily thought as the dwelling place of Adam.[48] The Quran refers frequently over various Surah about the first abode of Adam and Hawwa (Eve), including surat Sad, which features 18 verses on the subject (38:71–88), surat al-Baqara, surat al-A'raf, and surat al-Hijr although sometimes without mentioning the location. The narrative mainly surrounds the resulting expulsion of Hawwa and Adam after they were tempted by Shaitan. Despite the Biblical account, the Quran mentions only one tree in Eden, the tree of immortality, which God specifically claimed it was forbidden to Adam and Eve. Some exegesis added an account, about Satan, disguised as a serpent to enter the Garden, repeatedly told Adam to eat from the tree, and eventually both Adam and Eve did so, resulting in disobeying God.[49] These stories are also featured in the hadith collections, including al-Tabari.[50]

Latter Day Saints [edit]

Followers of the Latter Day Saint movement believe that after Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden they resided in a place known as Adam-ondi-Ahman, located in present-day Daviess County, Missouri. It is recorded in the Doctrine and Covenants that Adam blessed his posterity there and that he will return to that place at the time of the final judgement[51] [52] in fulfillment of a prophecy set forth in the Book of Mormon.[53]

Numerous early leaders of the Church, including Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and George Q. Cannon, taught that the Garden of Eden itself was located in nearby Jackson County,[33] but there are no surviving first-hand accounts of that doctrine being taught by Joseph Smith himself. LDS doctrine is unclear as to the exact location of the Garden of Eden, but tradition among Latter-Day Saints places it somewhere in the vicinity of Adam-ondi-Ahman, or in Jackson County.[54] [55]

Art and literature [edit]

Art [edit]

One of oldest depictions of Garden of Eden is made in Byzantine style in Ravenna, while the city was still under Byzantine control. A preserved blue mosaic is part of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Circular motifs represent flowers of the garden of Eden. The Garden of Eden motifs most frequently portrayed in illuminated manuscripts and paintings are the "Sleep of Adam" ("Creation of Eve"), the "Temptation of Eve" by the Serpent, the "Fall of Man" where Adam takes the fruit, and the "Expulsion". The idyll of "Naming Day in Eden" was less often depicted. Michelangelo depicted a scene at the Garden of Eden on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

-

After wandering through the Garden of Eden, Eve takes the forbidden fruit while Lilith speaks to Adam (by Carl Poellath, c. 1886)

Literature [edit]

For many medieval writers, the image of the Garden of Eden also creates a location for human love and sexuality, often associated with the classic and medieval trope of the locus amoenus.[56]

In the Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri places the Garden at the top of Mt. Purgatory. Dante, the pilgrim, emerges into the Garden of Eden in Canto 28 of Purgatorio. Here he is told that God gave the Garden of Eden to man "in earnest, or as a pledge of eternal life," but man was only able to dwell there for a shot time because he soon fell from grace. In the poem, the Garden of Eden is both human and divine: while it is located on earth at the top of Mt. Purgatory, it also serves as the gateway to the heavens.[57]

Much of Milton's Paradise Lost occurs in the Garden of Eden.

See also [edit]

- Antelapsarianism

- Christian naturism

- Epic of Gilgamesh

- Eridu

- Fertile Crescent

- Golden Age

- Heaven in Judaism

- Hesperides

- Jannah

- Nondualism

- Persian gardens

- Purgatorio

- Sacred garden

- The Summerland

- Tamoanchan

- Utopia

References [edit]

- ^ Metzger, Bruce Manning; Coogan, Michael D (2004). The Oxford Guide To People And Places Of The Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN978-0-19-517610-0 . Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ a b Cohen 2011, pp. 228–229

- ^ a b Wilensky-Lanford, Brook (2012). Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden . Grove Press. ISBN9780802145840.

paradise lust.

- ^ a b Hamblin, Dora Jane (May 1987). "Has the Garden of Eden been located at last? (Dead Link)" (PDF). Smithsonian. 18 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ a b Zevit, Ziony. What Really Happened in the Garden of Eden? 2013. Yale University Press, p. 111. ISBN 9780300178692

- ^ a b Duncan, Joseph E. Milton's Earthly Paradise: A Historical Study of Eden. 1972. University Of Minnesota Press, pp. 96, 212. ISBN 9780816606337

- ^ a b Scafi, Alessandro. Return to the Sources: Paradise in Armenia, in: Mapping Paradise: A History of Heaven on Earth. 2006. London-Chicago: British Library-University of Chicago Press, pp. 317–322. ISBN 9780226735597

- ^ Davidson 1973, p. 33.

- ^ Donald Miller (2007) Miller 3-in-1: Blue Like Jazz, Through Painted Deserts, Searching for God, Thomas Nelson Inc, ISBN 978-1418551179, p. PT207

- ^ Genesis 13:10

- ^ Isaiah 51:3

- ^ Ezekiel 36:35

- ^ Joel 2:3

- ^ Tigchelaar 1999, p. 37

- ^ "Latin Vulgate Bible with Douay–Rheims and King James Version Side-by-Side+Complete Sayings of Jesus Christ". www.latinvulgate.com . Retrieved 2021-03-10 .

- ^ Levenson 2004, p. 13 "The root of Eden denotes fertility. Where the wondrously fertile gard was thought to have been located (if a realistic location was ever conceived) is unclear. The Tigris and Euphrates are the two great rivers of the Mesopotamia (now found in modern Iraq). But the Piston is unidentified, and the only Gihon in the Bible is a spring in Jerusalem (1 Kings 1.33, 38)."

- ^ Bible, Genesis 2:9

- ^ Bible Genesis 3:24

- ^ Hebrew Bible, Genesis 2:10–14

- ^ "The Jewish Quarterly Review". The Jewish Quarterly Review. University of Pennsylvania Press. 64–65: 132. 1973. ISSN 1553-0604. Retrieved 2014-02-19 .

...as Cossaea, the country of the Kassites in Mesopotamia [...]

- ^ Speiser 1994, p. 38

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews. Book I, Chapter 1, Section 3.

- ^ Lars-Ivar Ringbom, Paradisus Terrestris. Myt, Bild Och Verklighet, Helsingfors, 1958.

- ^ Ezekiel 28:12–19

- ^ Stordalen 2000, p. 164

- ^ Brown 2001, p. 138

- ^ Swarup 2006, p. 185

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 61

- ^ Hebrew-English Bible Genesis 2:10–14

- ^ Day, John. Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. 2002. Sheffield Academic Press, p. 30. ISBN 9780826468307

- ^ Cline, Eric H. (2007). From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. National Geographic. p. 10. ISBN978-1-4262-0084-7.

- ^ Bergreen, Lawrence (2011). Columbus: The Four Voyages, 1493–1504. Penguin Group US. p. 236. ISBN978-1101544327.

- ^ a b "Joseph Smith/Garden of Eden in Missouri", FairMormon Answers

- ^ Shaw, Jane (2012). Octavia, Daughter of God. Random House. p. 119. ISBN9781446484272.

- ^ Gloria Jahoda, The Other Florida, chap. 4, "The Garden of Eden." ISBN 9780912451046

- ^ "Jerusalem as Eden". 24 August 2015.

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 96.

- ^ Cohen 2011, p. 229.

- ^ a b Gan Eden – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.

- ^ Olam Ha-Ba – The Afterlife - JewFAQ.org; 02-22-2010.

- ^ a b Eshatology – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.

- ^ "Gehinnom is the Hebrew name; Gehenna is Yiddish." Gehinnom – Judaism 101 websourced 02-10-2010.

- ^ "Gan Eden and Gehinnom". Jewfaq.org. Retrieved 2011-06-30 .

- ^ "End of Days". Aish. 11 January 2000. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Qur'an, 2:35, 7:19, 20:117, 61:12

- ^ See list of occurrences.

- ^ Patrick Hughes, Thomas Patrick Hughes Dictionary of Islam Asian Educational Services 1995 ISBN 978-8-120-60672-2 p. 133

- ^ Leaman, Oliver The Quran, an encyclopedia, p. 11, 2006

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon Mecca and Eden: ritual, relics, and territory in Islam p. 16, 2006

- ^ "Doctrine and Covenants 107:53".

- ^ "Doctrine and Covenants 116:1".

- ^ "Daniel 7:13–14, 22".

- ^ Bruce A. Van Orden, "I Have a Question: What do we know about the location of the Garden of Eden?", Ensign, January 1994, pp. 54–55.

- ^ "What is Mormonism? Overview of Mormon Beliefs – Mormonism 101". www.mormonnewsroom.org. 2014-10-13. Archived from the original on 2012-03-10. Retrieved 2018-10-31 .

- ^ Curtius 1953, p. 200, n.31

- ^ "Dante Lab at Dartmouth College: Reader". dantelab.dartmouth.edu . Retrieved 2021-11-06 .

Bibliography [edit]

- Brown, John Pairman (2001). Israel and Hellas, Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN9783110168822.

- Cohen, Chaim (2011). "Eden". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199730049.

- Curtius, Ernst Robert (1953). European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages . Princeton UP. ISBN978-0-691-01899-7. Translated by Willard R. Trask.

- Davidson, Robert (1973). Genesis 1-11 (commentary by Davidson, R. 1987 [Reprint] ed.). Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521097604.

- Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: Introduction and Annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible . Oxford University Press. ISBN9780195297515.

- Mathews, Kenneth A. (1996). Genesis. Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman & Holman Publishers. ISBN9780805401011.

- Smith, Mark S. (2009). "Introduction". In Pitard, Wayne T. (ed.). The Ugaritic Baal Cycle, volume II. BRILL. ISBN978-9004153486.

- Speiser, E.A. (1994). "The Rivers of Paradise". In Tsumura, D.T.; Hess, R.S. (eds.). I Studied Inscriptions from Before the Flood. Eisenbrauns. ISBN9780931464881.

- Stordalen, Terje (2000). Echoes of Eden. Peeters. ISBN9789042908543.

- Swarup, Paul (2006). The self-understanding of the Dead Sea Scrolls Community. Continuum. ISBN9780567043849.

- Tigchelaar, Eibert J. C. (1999). "Eden and Paradise: The Garden Motif in some Early Jewish Texts (1 Enoch and Other Texts Found at Qumran)". In Luttikhuizen, Gerard P (ed.). Paradise Interpreted. Themes in Biblical narrative. Leiden: Konninklijke Brill. ISBN90-04-11331-2.

- Willcocks, Sir William, Hormuzd Rassam. Mesopotamian Trade. Noah's Flood: The Garden of Eden, in: The Geographical Journal 35, No. 4 (April 1910). DOI: 10.2307/1777041

External links [edit]

- Smithsonian article on the geography of the Tigris-Euphrates region

- Many translations of II Kings 19:12

- "Eden". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

Why Doesnt My Back to Eden Garden Grow

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garden_of_Eden

0 Response to "Why Doesnt My Back to Eden Garden Grow"

Post a Comment